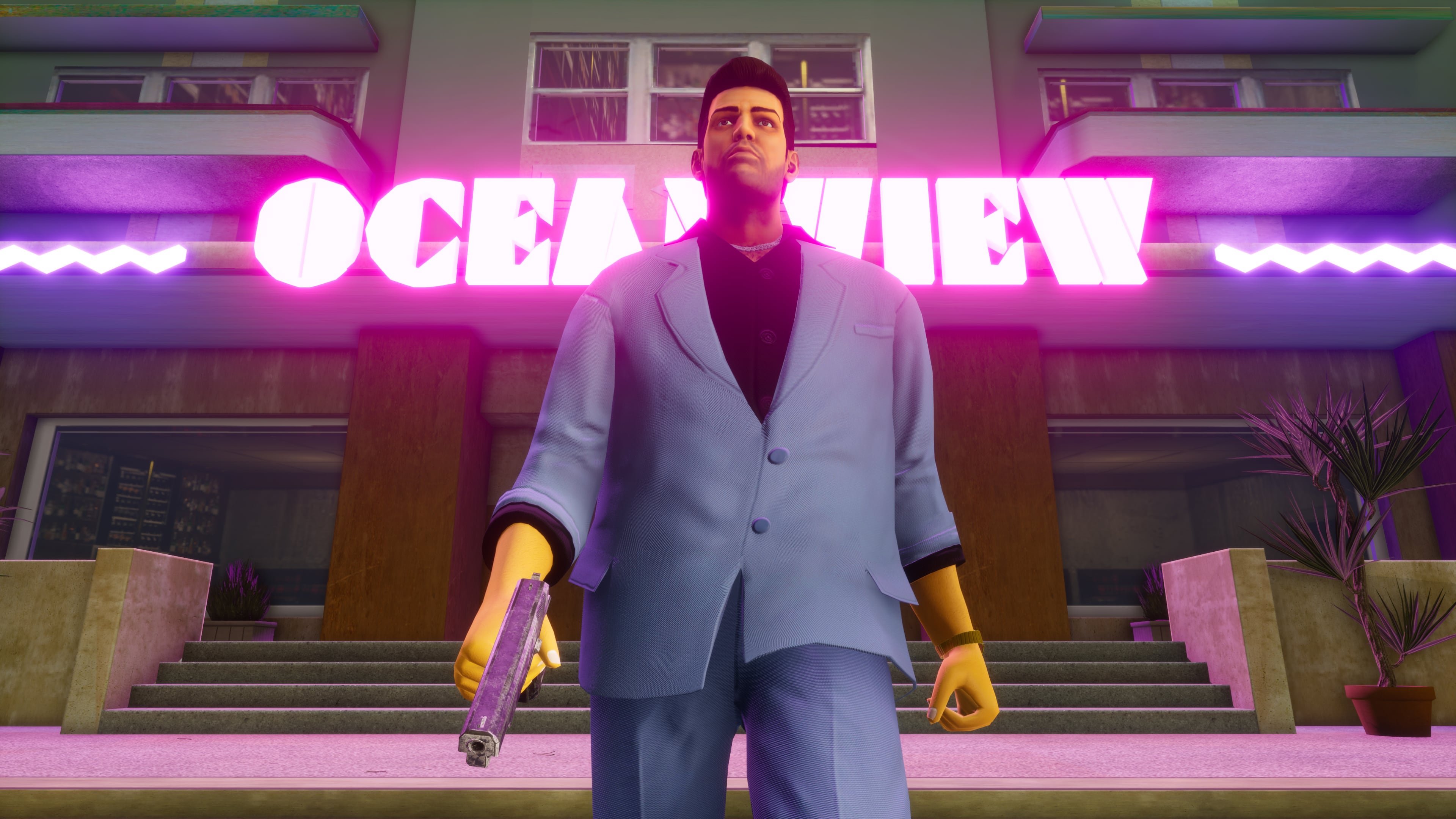

We felt inclined to defend video games as a medium back then, as it always seemed precariously balanced on the cusp of mainstream acceptance, never quite tipping over (see: blowjobs, murder). Nowadays, the form no longer has anything to prove: its legitimacy is self-evident, and needs no grasping-at-straws intellectualising. But evidence of its unrefined, uncouth past remains in abundance – particularly in its long-toothed mainstays. Grand Theft Auto is so old that it carries its legacy jokes in the same way that Windows 11 features an MS-DOS command prompt. It’s a world in which the stockmarket is called BAWSAQ; a sort of school jotter gag more likely to raise an acknowledging “hm” than a real laugh, and not exactly a deft skewering of late capitalism. I’m not sure it even works outside of Scotland. But BAWSAQ and choose-your-own-adventure prostitution persist as heritage markers in a game universe that has, against all expectation, matured and refined over the years as the world it intended to darkly mirror degenerated into a screaming parody of itself. This is a series which started with silent protagonists existing only as a conduit for player agency, but grew so invested in its character arcs that it came to embody the term “ludonarrative dissonance” – wankspeak for the phenomenon of player action being incongruous to character motive. E.g. GTA 4’s Niko Bellic: PTSD suffering former child soldier of the Yugoslav Wars, in America seeking a better life. Hobbies: waging a bloody one-man war against the LCPD for no apparent reason. As an aside, ludonarrative dissonance is an overblown problem. Audiences are smart enough to understand 9000 different Spider-Man continuities running concurrently; people are more than equipped to make a distinction between player freedom and narrative rigidity. Existing somewhere in the space between them is something beautiful that only video games can do, and something innately understood by an audience which has never known a world without them. What isn’t overblown is the existential issue that satirists of all kinds face; that the real world is now absurd beyond parody. Armando Iannucci (another Scottish export famed for parodying America as an observant outsider) said as much back in 2016 when asked about the prospect of a post-coalition revival of The Thick of It: “I now find the political landscape so alien and awful that it’s hard to match the waves of cynicism it transmits on its own.” For context, this was said in the weeks before Brexit became a reality, when the presidency of Donald Trump was generally regarded as a remote possibility. At the mere prospect of what was to come, the world’s leading comedy writers were already throwing in the towel. Five years, countless crises, a pandemic, an endless string of fatuous SNL sketches, and a bizarrely jokeless revival of Spitting Image later, it’s hard not to conclude that satire is dead. Love or hate the man (and you shouldn’t love him), Donald Trump himself was effortlessly funnier than anyone writing lines for his Spitting Image puppet, and visibly more grotesque than Alec Baldwin in a fatsuit. He’s not funnier than a Jetski company being called “Speedophile”, though. This is where GTA may be perfectly and uniquely placed to take on reality: it’s already laced with crass incongruity, its very molecules teeming with bizarre juxtaposition. In this world, there’s a kids cartoon where space marines conquer the galaxy in a giant dildo. There are two car manufacturers whose names are misspellings of ’anus’, a clothing firm called “ProLaps”, and an airline called “Air Biscuit”. And yet, while becoming no less obsessed with scatological puns, the series has spent well over a decade in the process of morphing into something reminiscent of prestige television drama. GTA 3 and Vice City honed Rockstar’s gold standard of world building, but had little more to say than letting us all know how much Dan Houser loved Scarface. San Andreas built on that foundation by demonstrating some serious dramatic chops – a touching story about loss and rediscovering your roots, which admittedly skirts around race relations in America in a way that would be considered cowardly now but at the time was considered bold merely for featuring a black protagonist – from a black neighbourhood – and being steeped in the gangsta rap culture of the early 90s. Indeed, a minority of white players complained about CJ’s race on the grounds that they could not relate to him, unwittingly making the case for why representation matters, as those sorts of idiots tend to do (it’s worth noting that Tommy Vercetti being Italian, or Niko Bellic being Serbian, did not inspire similar outcries). Rockstar’s gritty follow-up to San Andreas, GTA 4, a filth-caked reimagining of Liberty City’s composite East Coast vibe pushed the series further into the vein of prestige HBO dramas like The Sopranos and The Wire, both of which were enjoying the height of their popularity during the game’s development. Pushed too far, argued many: Niko’s escape from war-torn Eastern Europe into the squalor of post 9/11 American decline was a serious tale for serious times, and caused a backlash among many of those who desire little else but dizzy escapism from their billion-dollar murder simulators, a backlash which Saints Row capitalised on by veering full-throttle into neon-saturated surrealism (which didn’t stop it being a load of soulless rubbish unfit to lick GTA’s boots, but I’m glad it found its niche). More recently, GTA-with-horses sequel Red Dead Redemption II gave us an almost experimental take on the formula by making us live out the last days of a protagonist dying from tuberculosis – and it was their finest work to date. Arthur is a joyous character to inhabit; his story resolutely fulfils the “redemption” promise of the title, and there’s nothing quite so endearing as the glee he exudes while sitting in a tin bath. There’s no shortage of evidence that Rockstar’s flair for the dramatic is as vibrant as their love for nob gags and pratfalls, and that they thrive not at a mid-point between the two extremes, but by pivoting at will from one to the other while somehow keeping it all perfectly consistent, like a dancer pirouetting beautifully in the air while wearing a stupid hat. The world of Grand Theft Auto is just a funny place to play in, for creator and audience alike. Whether or not the world it’s meant to satirise has somehow grown too stupid to earnestly make fun of is rather beside the point; the next GTA will – as a gift from its predecessors – have the bandwidth to choose how earnest it is from moment to moment. Whether Rockstar is still acrobatic enough to pirouette from one tone to another is still up in the air (what with its lead writer Dan Houser moving on from the firm in 2020), but the signs from GTA Online aren’t discouraging on this front: Lamar and Franklin’s dialogue in the latest Short Trips co-op campaign is hilarious, at least (even if the rest of the content is phoned-in rubbish, one hopes because the studio is full steam ahead on the sequel). Grand Theft Auto has demonstrated that it has the agility to defy a world that killed parody, and sufficient distance from it that it barely matters. Regardless, GTA 6 will not be launching in a vacuum: its legacy matters, and imbues it with the power to overcome an inevitable suspicion that nothing it does can be more absurd or obscene than business-as-usual in the post-Trump world. Because of course it can you idiot, there’s a jetski company called “Speedophile”.