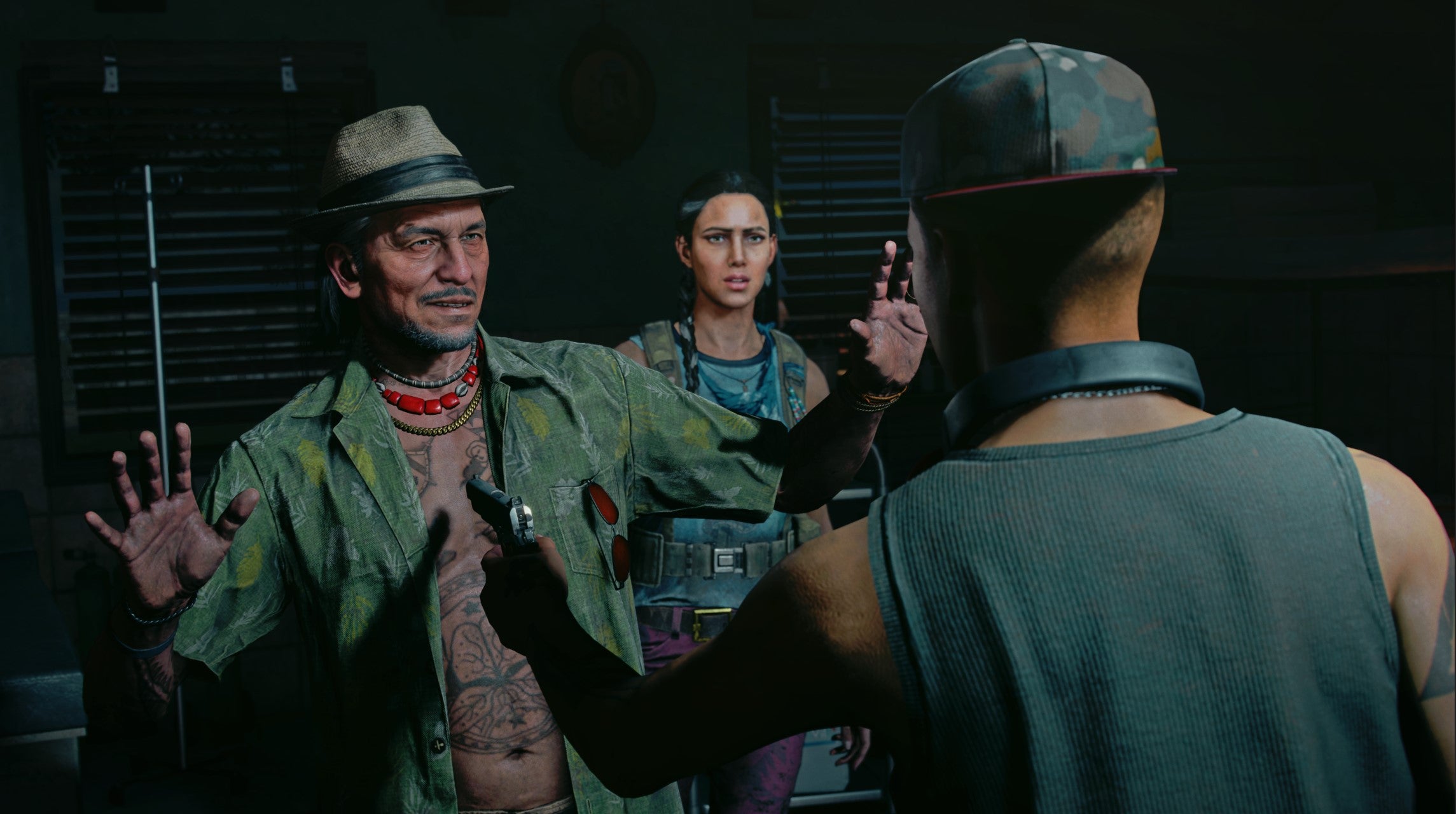

Far Cry 6’s paradise hinges on fantasies — the fantasy that one man can shape fate, that corruption can be overturned, and that you’ll believe the situation on Yara is deeper and more complex than it really is.. The latest in Ubisoft’s long-running franchise refines the series’ penchant for chaos, but the fight against Castillo is far from the only civil war taking place here. Far Cry 6 is at odds with itself as well. Far Cry 6 begins with a bang, or, more accurately, hundreds of them. Government soldiers raid a mid-sized city on Yara’s main island, ostensibly hunting rebels, but actually capturing dissidents and outcasts as labor supplies for Antón Castillo’s work camps. Dani escapes with her friends and fellow orphans, before ending up alone on Isla Santuario, a government outpost off the Yaran coast. Her sole mission is making it as far away from Yara as possible, but she can only do that with help from Libertad, the guerrilla revolutionary group bent on destroying Castillo and everything he stands for. Dani is a first for Far Cry in many ways. She’s a vulnerable and reluctant participant, rather than an overpowered “chosen one” hero, and watching her ease into the role of liberator throughout the game makes for a satisfying narrative arc, even though her character growth is limited and predictable. Despite his central role (and Hollywood casting), Castillo doesn’t steal the show, at least not all the time. Giancarlo Esposito’s performance as the unpredictable and brutal dictator is captivating, but Castillo is a villain we’ve seen before. What’s of more interest is the themes Far Cry 6 tries addressing and the people it uses in the process. Far Cry 6 touches on a surprising range of topics in weaving its tale of revolution, from the middle class’ role in fueling rebellion to the process of institutionalizing division and notions of the “other.” Yara’s Libertad are idealists, but grounded ones who recognize removing a corrupt regime is far from the last act of a successful rebellion. They’re also progressive, providing homes and a purpose for Castillo’s so-called undesirables, including LGBTQ+ Yarans disowned by their families. It’s a shame, then, that Ubisoft doesn’t carry this narrative further. There’s potential for a unique perspective on war, politics, and society buried in Far Cry 6 that most video games and media in general tend to avoid. However, it’s still a Far Cry game before it’s anything else. Recognizing these factors exist is as deep as Far Cry 6 goes, and this is where it relies on the idea of guerrilla fantasy to hold itself together. There’s just enough suggestion of depth in the characters and their struggles, but anything beyond what you briefly see and hear is your responsibility to provide. You see this the most with optional guerrilla objectives, Dani’s opportunities to dismantle Castillo’s regime at its foundation. One set of tasks in Valle de Oro targets Maria Marquessa’s propaganda machines, including a film studio and broadcast station. Clara urges you to do as much damage as possible, both to show Castillo you mean business and to hamper his propaganda efforts in the region, but you’re left imagining the effects. Dani’s actions earn Libertad a new base, some fresh intel on hidden caches — and nothing more. There’s no change in Castillo’s broadcast abilities, no influence over guerrilla efforts, and not even the Matanzas, the group you’re aiding, recognize what you’ve accomplished. It’s the same across Yara’s other regions. There’s a sense of disconnect between your guerrilla work and the sub-stories about Yara’s culture and people Ubisoft tries telling, and it highlights the limits of adhering to the series’ familiar structure. Despite its shortcomings, Far Cry 6’s guerrilla fantasy is still hypnotic, with some outstanding moments as well. The set-piece that ends the tutorial genuinely had me on the edge of my chair, and arriving in Esperanza the first time inspired a sense of awe, dread, and anticipation as the magnitude of the task in front of you slowly becomes apparent. Castillo’s regime and the horrors it inflicts are despicable enough where you feel invested in Dani’s fight. Every encounter with Castillo’s soldiers feels like a small victory for the people, even though you know it has no value outside letting you play with big guns. Granted, playing with the big guns — and the small ones, and the gas-powered ones — is incredibly fun on its own and makes Far Cry 6 the epitome of chaos sandbox. Dani gets the standard sniper rifles and shotguns over the course of her journey. Mods ranging from poison ammo to high-powered scopes help keep combat interesting by providing endless methods of approaching each task, but it’s the rare, pre-modded Resolver weapons that stand out the most. The motorized crossbow literally blows enemies away, while the nailgun rivals any submachine gun Dani can swipe from Castillo’s army. A personal favorite is the Resolver revolver, a monster of a handgun paired with a metal riot shield that replaces Dani’s machete attack with an overpowered punch. Yara might be vast and beautiful, but these weapons, created with scraps, leftover uranium, and a touch of Juan Cortez’s unstable genius, are what give Far Cry 6 its strongest sense of place and emphasize the struggle’s guerrilla roots more than anything else. Take the Supremo, for example. It’s a kind of ultimate weapon cobbled together from garbage and glue — finding Supremo Bond adhesive is actually required to upgrade it — that launches baseballs and dynamite. It also feeds on the blood of your enemies, because of course it does. This isn’t even going into the trained attack companions, wild tank rides across Yara’s countryside, gliding into restricted airspace using a wingsuit, or the dozens of other outrageous things Dani can do in the name of liberation. The problem is where she’s doing them. Ubisoft isn’t trying to hide the similarities between Yara and Cuba: the colonized Latin island with a prized agricultural crop, the mid-century revolution that propelled a militaristic tyrant into power, American trade restrictions, Miami as the first stop for refugees, and countless others. Far Cry 6’s themes are universal, arguably even more applicable to contemporary American society than anywhere else. There’s no discernable reason for choosing not-Cuba as the setting. At worst, it subtly reinforces stereotypes framing Latin American nations as war-torn and corrupt without the necessary narrative depth to explore the factors that cause these conflicts to begin with. It’s illustrative of the broader conflict Far Cry 6 finds itself facing with, well… itself. It wants to spin a more involved narrative, but steps back before things get too serious. Yaran Stories hint at deeper worldbuilding, though adhering to the standard Far Cry and open world structure means staleness creeps into exploration and guerrilla activities. Juan Cortez was more accurate than he realized when he recruited Dani to Libertad. Far Cry 6 prefers playing guerrilla over more serious reflection because “blowing up shit is fun,” and Ubisoft just isn’t quite ready to give that up yet. Disclaimer: Tested on Xbox Series S, with a copy of the game provided by the publisher. Also available on Xbox One, Xbox Series X, PS4, PS5, and PC.